Without exception

Reading

Driven by curiosity, whenever people feel perplexed, they tend to look for causes and an exit. When an author writes a book, perhaps it isn’t to “find readers,” but to let readers find them. When we look up at the stars, there is Thoreau and Li Bai; when life feels unbearable, there is Milan Kundera and Kafka; when we are in love, there is Nalan Xingde and Li Shangyin. Each time we read, we often feel a deep resonance. Our feelings find a listener on the other side of time, and with it comes a strong sense of safety.

Looking across what survives in writing, sustained high-pitched passion seems to exist only in manifestos. The reason is probably simple: people are, by nature, confused.

Commentary

I resist writing argumentative essays; narrative feels lighter, effortless. My thesis proposal is over and I’m close to graduating. I’m simply recording things—life paths differ, so there’s probably little “transfer learning signal” for others. But if, by chance, it resonates, I’d be happy. Lately I’ve started thinking about a calling. Of course, I won’t force it, and I don’t expect it. I also feel that once I begin weighing pros and cons, the calling seems to disappear. What follows are some recent thoughts—unanswered, repeatedly shifting. When you’re lost with no direction, the lostness becomes the direction.

This contains long stretches of rational analysis. If I were a reader, I probably wouldn’t finish it. It’s self-audit and writing practice. I’ll try to list points plainly, avoiding syrupy sentimentality or affectation. The theme is career choice (making money). Intended readers: ordinary people.

Distribution

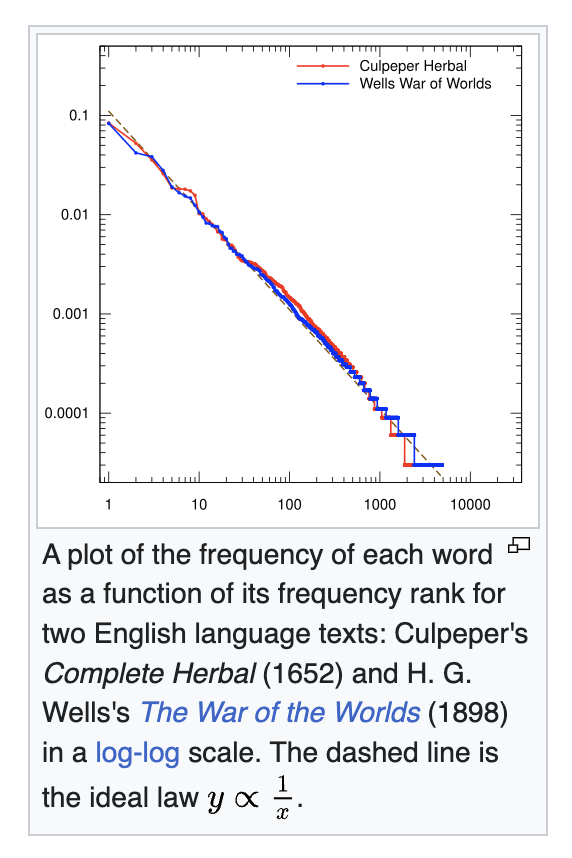

Human vocabulary follows a long-tail distribution: a tiny fraction of words get used again and again.

So does wealth: a tiny fraction of people controls most of it. Because the overall distribution is stable and changes only marginally, the probability of an individual “jump” within the distribution is also long-tailed. Take startups: it’s life-or-death nine times out of ten. Yet because of survivorship bias, we feel as if success isn’t so extremely distributed. We then try to distill “lessons” from the few successes, deepening the bias. In the long run, most startups vanish, and most founders regress to the mean. In 2025, the baseline to regress to is relatively high in tech; at the same time, volatility above that baseline is larger. From another angle, survivorship bias feels even stronger. When winners shout, silence is the majority.

Individuals

As individuals in a long-tail distribution, our “position” moves with the random events we choose to participate in (for example, buying leverage is participating in a long-tail event; if your wealth grows exponentially, you move within the sample). Of course, the outcome is determined by the event itself. If you choose a relatively stable job, you’re taking on low-risk volatility. If you join a startup, you’re entering a collective game—and the game is often long-tailed. During participation, it rarely feels long-tailed; you may even feel it must succeed. Beyond randomness, the size of the stake determines the magnitude of the swing.

Change

Trying to change the long-tail distribution itself through individual effort (as if reducing risk to near zero) is often futile. There are many ways to participate in long-tail events: opening a board game café or a milk-tea shop; buying 10x leverage; feeling you “missed” the AI get-rich wave because you studied materials science—then taking the cash you saved and buying 10x leverage in public markets to participate in a long-tail event.

The effort an individual can make (but doesn’t have to) is often to place oneself into the random events one wants to join. Since we can’t change the probability distribution, what we can do is expand our eligibility to participate in more long-tail events. More importantly: obtain the eligibility with the lowest cost and the highest upside. For example, joining a startup and receiving early equity: your cost is earning an interview and passing it, and your upside ceiling can be very high—though you pay with time and health. Once you have initial capital, you can also invest in startups; the upside ceiling may be similar, the investment can go to zero, but you don’t pay as much time or health.

Since we can’t change the distribution of random events, we should hand outcomes over to fate. A better goal during growth is to continuously broaden your set of choices of random events. Good events are low-cost, high-upside. Joining an industry, opening a milk-tea shop, placing a 10x leveraged bet, selling masks, selling Labubu—these are all random events. Everyone should find the random events whose costs fit them. Random events are everywhere. Even if you enter an ideal event, you still won’t escape the overall long-tail reality.

Without exception

Words are only one medium for resonance; the carriers that produce the most resonance are what survive. Beyond writing, films like The Silence of the Lambs and Let the Bullets Fly are watched repeatedly because they carry resonance. Beyond media, the Colosseum and the Great Wall also carry resonance—attempts to remember the imprint of human nature. Beyond tragedy, roles on the opera stage and rituals offered to the sky are also human longing.

I think we should never underestimate human greed. There’s no need to envy others, and no need to believe we are uniquely special. The imprint won’t be erased; confusion and Without exception are the norm. In the maze, you and I are not special. So after understanding the distribution and reconciling with impermanence, feeling becomes supreme.