About Su Shi (1037–1101)

Ice pops

In elementary school, memorizing and copying Tang and Song poetry was mostly just homework. Yet those dutiful, half-hearted recitations sparked in a worldly kid like me a quiet longing for fields and mountains.

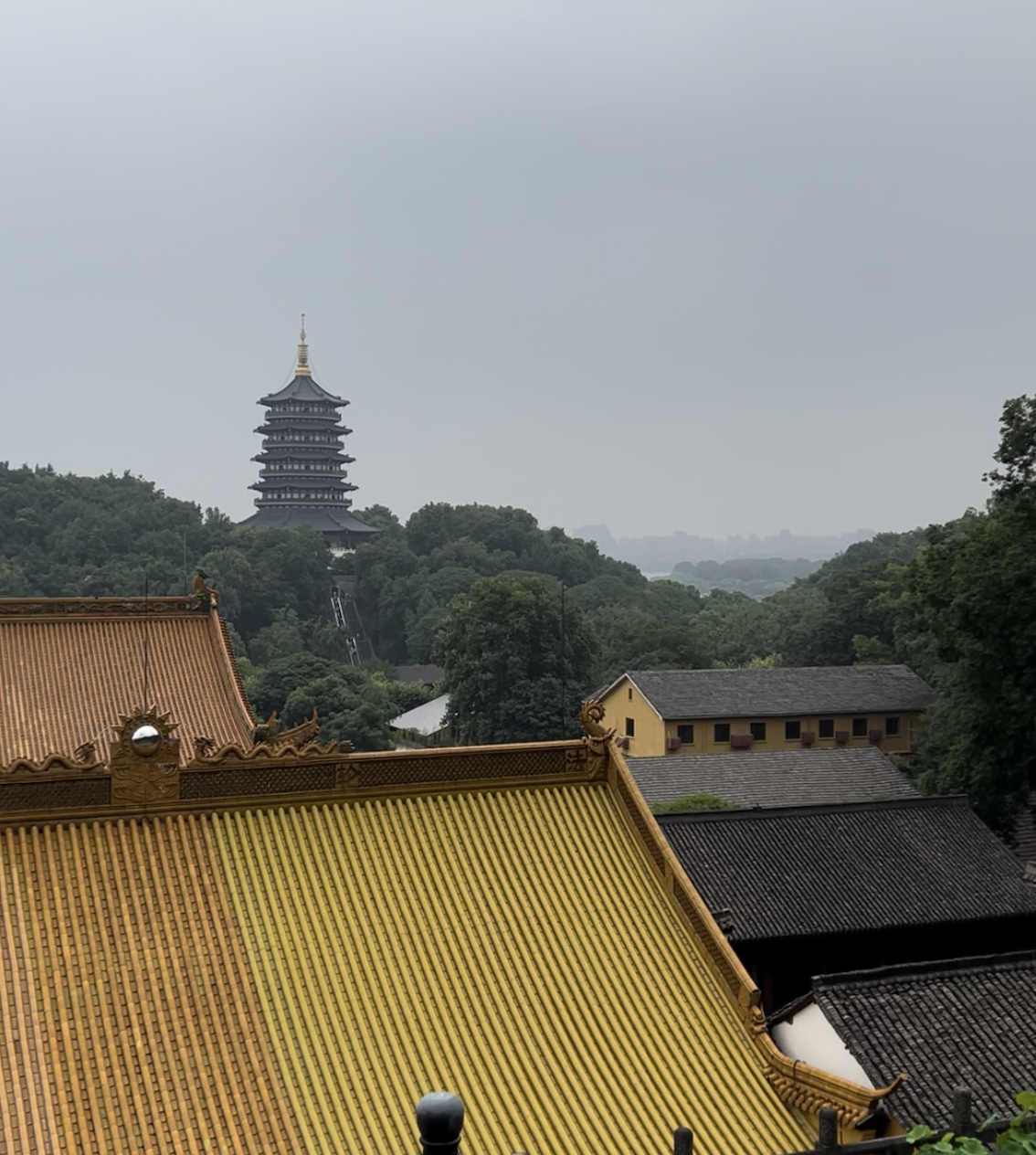

Su Shi (Su Dongpo) and Hangzhou are inseparable. When I was little, my parents forced me to take traditional painting lessons at the Children's Palace. Sometimes we sketched near Su Xiaoxiao's pavilion, where the lotus blooms form a semicircle with the pavilion at the center of Su Causeway. I never painted very seriously; people streamed by on the causeway, and I felt as though I were joining the bustle, perched on a tiny stool, gazing at the flowers. Later, every year there was a West Lake fireworks show. My parents had friends in an old house on Baoshuta Road, and we would cram onto their balcony to watch. Spectators filled every patch of greenery along the lake—the willows of Su Causeway and the Broken Bridge packed tight. Eventually environmental rules and the shift of the city center ended the fireworks festival. When I grew older, I often went to Jingci Temple by the lake. The Guanyin Hall at the top looks out over City God Temple, Leifeng Pagoda, the whole of West Lake, and Su Causeway. Jingci isn't as famous as Lingyin, so it's quieter—good for both triumph and retreat, a place to settle the mind. Su Shi spent only a few scattered years in Hangzhou, yet the lives of many locals still revolve around his traces.

Summer in Hangzhou is sweltering, and the mosquitoes swarm at night. But on Su Causeway you can stroll with two or three friends, each holding an ice pop, teasing the couples on the benches, then turn back the way you came. The evening breeze and moonlight are eternal, heaven and earth ever-mysterious.

All are just feelings

Su Shi's life rose and fell. At twenty he ranked in the top three of the nationwide exams and even earned the emperor's praise—"a poet seen once in a hundred years." In modern terms, he peaked the moment he debuted. His late-career poems reveal that in youth he too boasted of his "heroic bearing" and could, with friends, "laugh as warships turned to ash." Yet early glory also made him more open-minded. In his twenties he wrote that "life should be like a goose's fleeting trace in snow." Fame and fortune are but smoke; a life ought to drift, leaving only faint prints. Of course, among cups of wine scholars still "unleash youthful madness," daring "to draw a full bow and shoot the Sirius star to the northwest."

These immortal lines show his breadth of spirit—on one side the ambition of "who else but me," on the other the delicate West Lake, "light or heavy makeup both becoming." One moment he leads hunting hounds and eagles; the next he stands in drizzling mist by the lake, "a lone cloak in rain."

Mid-career, the "Crow Terrace Poetry Case" upended his life—banished to Huangzhou, his brilliant prospects shattered. Such dramatic arcs, coupled with Su Shi's keen sensitivity, make his later poetry irresistible to me. He was a multi-talented young professional avant la lettre: skilled, well read, socially adept, literary to the core, able to craft lines for the ages. Then suddenly the curtain fell. From the heights of court he plunged to a prisoner in plain clothes. That tension draws me to the poems of his exile (perhaps I just enjoy others' hardships). Within the measured tones lie reflections on an extraordinary life. I prefer watching how people face adversity, not the syrup of success stories. We seldom hear the voices of once-famous figures who now speak from helplessness. Su Shi's verse is exactly that.

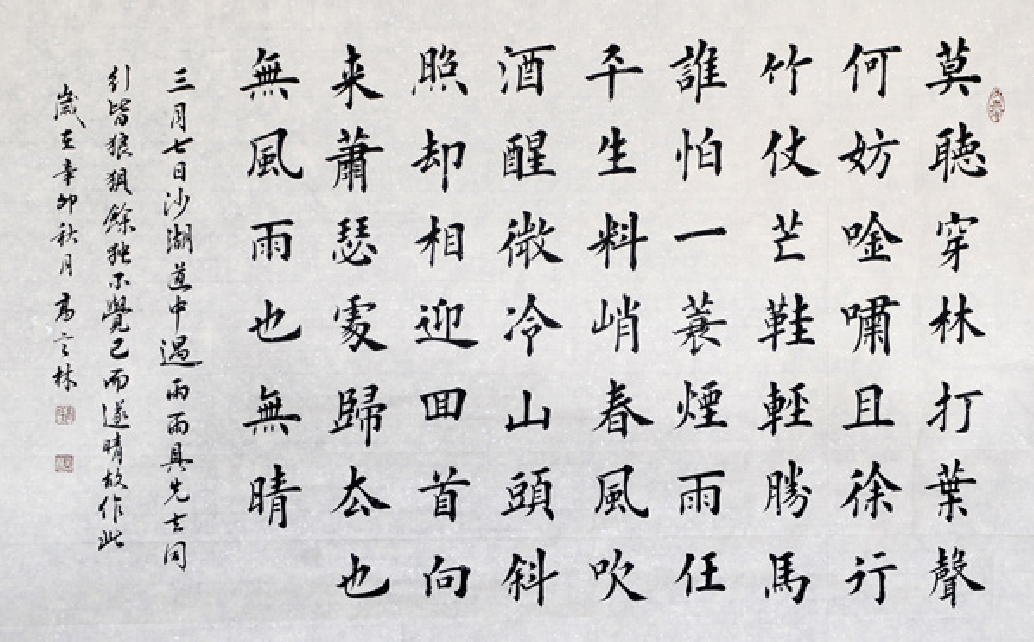

Among all poetry, my favorite is his "Song of the Wind and Rain" (Ding Feng Bo), especially its closing line. Here is my current prose rendering. It was written two years into Su Shi's exile in Huangzhou. On the third day of the third lunar month he and friends went on an outing and were caught in a sudden shower, which moved him to compose the poem.

"On March 7, I was out on the Shahu Road with friends when fine rain began to fall. Some, carrying umbrellas, hurried off; those without could only press on, grumbling and bedraggled. I, however, felt otherwise. Soon the sky cleared, and inspired, I wrote this piece.

"Walking through the woods, raindrops pattered on leaves. While my companions cursed the weather, I thought one should sing loudly in the wilds, stride on regardless of wind and rain. Lacking umbrellas or swift horses, we still had our bamboo staffs and our own two feet; to me that was lighter travel. Let the storm grow stronger—I would not resist. Rain drummed on my coarse cloak, yet I trudged on with a calm heart, silently repeating these thoughts as I walked.

"Before long the spring breeze rose, sobering the wine in me; my clothes were soaked and I felt a chill. Reaching the hilltop, the rain stopped and the slanting sun broke through, as if greeting us. I paused to enjoy the view, then decided to turn back. Looking down the path we had come, I still heard rain among the trees. 'Let's return the same way,' I thought. After all, wind or sun, rain or shine, they are merely different sensations. In life there is no real storm and no true clearing. When it rains, you walk in rain; when it clears, you walk in sunshine. Everything is feeling. All I need is to follow change, stay present, and keep moving."

All is just emptiness

Jiangnan's misty rains: whenever it rains I recall this poem. California sees little rain, so I treasure every shower. In the Heart Sutra there is the line: "With no obstructions in the mind, there is no fear." True fearlessness requires a mind without hindrance. Pain, I think, also springs from hindrance—inner wind and rain. Yet to have no hindrance is not to flee the world; first engage, then transcend. Just as the opening of Ding Feng Bo advises: walk through the rain; when fear creeps in, remind yourself these are only sensations; life is woven of sensations—go and savor them.

I grew up in a family of everyday piety. As a child in temples I would say, "Please let me score full marks on the test." Older now, I shed some of that worldly smoke and even reversed roles: I stop my elders from praying for me. Instead, I press my palms together and silently think, "Thank you for watching over all beings; may I accept whatever karma comes." Then I rise and leave. Behind me people squeeze in with incense and countless petitions. I hurry out—left foot in, right foot out. In the rain, West Lake is just as in my childhood. I pause and watch the crowd scurry by.